The Liberator

Martin Filler on Frank Gehry

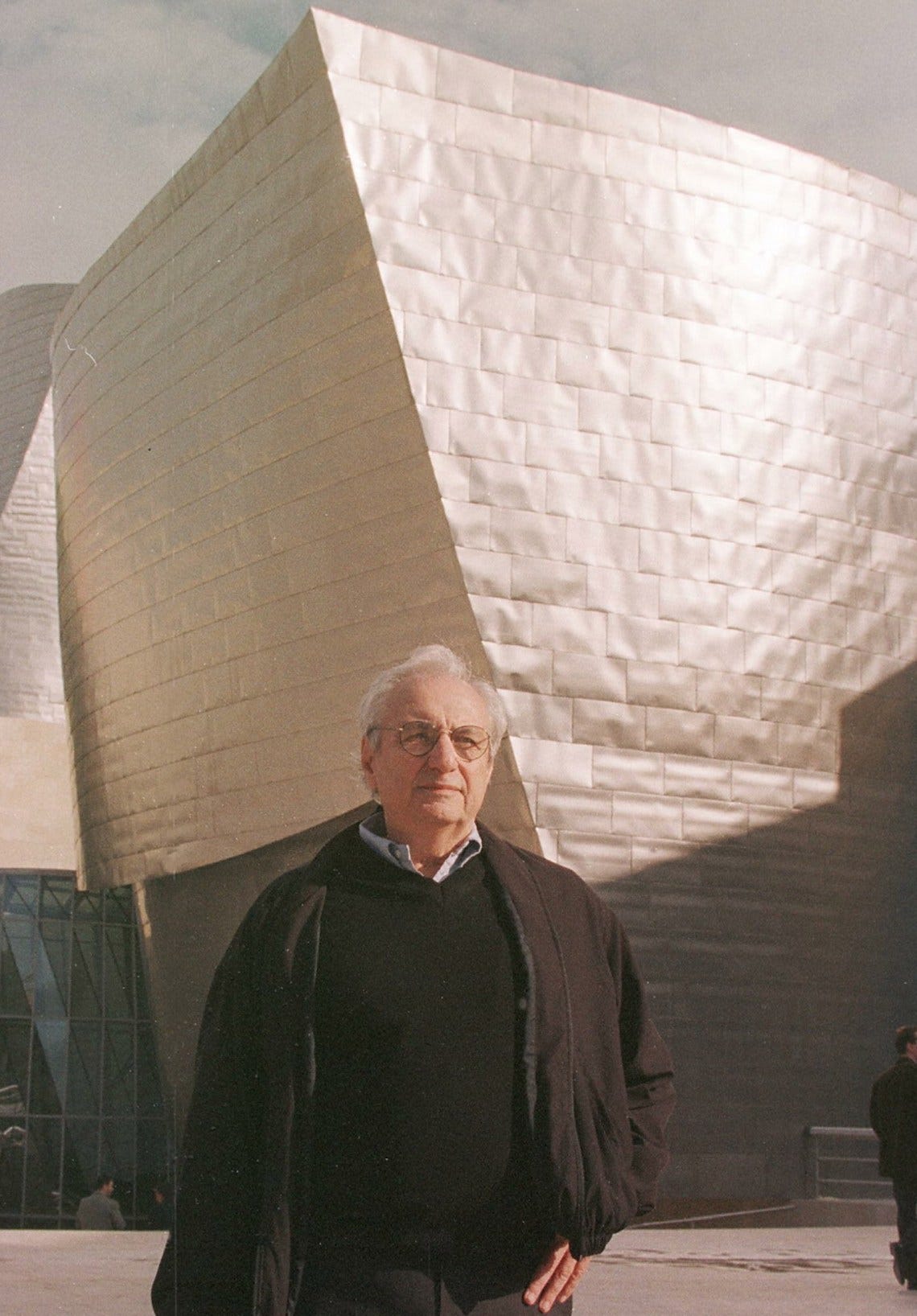

This week on the NYR Online, Martin Filler eulogizes Frank Gehry, who died on December 5, age ninety-six. Filler traces the development of Gehry’s style, from the “punk rock” architecture of the Seventies—“exaggerated, off-kilter forms executed in cheap materials such as corrugated metal”—to his Eighties collaboration with Claes Oldenburg to his inauguration “as the last great architectural titan of the waning millennium” with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in the Nineties. Along the way Filler details the nearly fifty-year professional relationship the two shared, wavering between critical distance and friendship.

One of the first things I thought of when I heard that Frank Gehry had died was a line from Orson Welles’s 1941 masterpiece, Citizen Kane. A reporter visits the title character’s former business manager, Mr. Bernstein, to interview him following the newspaper mogul’s death, and he comments that the old man had known Kane since the beginning. “From before the beginning, young fellow,” Bernstein interjects. “And now, it’s after the end.”

I first met Gehry in 1979, when I was a young editor at Progressive Architecture magazine, where my colleagues and I concurred that he was the most gifted of a new generation of architectural aspirants in this country. We were taken by his boldly original approach, which juxtaposed exaggerated, off-kilter forms executed in cheap materials such as corrugated metal, unfinished plywood, chain-link fencing, and chicken wire glass—the architectural equivalent of punk rock, then in its heyday. We were also convinced, however, that his aggressive aesthetic would never catch on with the masses and that he was destined to remain an esoteric cult figure at best. Little did we know that he’d ultimately become a household name among people who had heard of few architects other than an earlier Frank—Lloyd Wright.

The great liberator of late-twentieth-century architecture, Gehry was a latter-day Alexander who sliced through the Gordian Knot formed by an exhausted Modernism intertwined with a callow Postmodernism. Instead of trying to untangle those two discordant stylistic visions, which wastefully dominated American architectural discourse during the 1970s and 1980s, he showed an exhilarating way forward with freeform designs that drew on advanced contemporary art as their primary source of inspiration. He made the world safe for oddball buildings, and whatever one might think of the idiosyncratic architecture by the generation who followed him—Santiago Calatrava, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Thom Mayne, and their ilk—their careers would be unthinkable without the precedent he set.

Although his dramatic departure from architectural convention was at first confrontational and forbidding, it gradually became more buoyant and embracing. As his clients’ budgets increased and he moved from corrugated metal to shiny titanium, unfinished plywood to polished Douglas fir, and rubber matting to travertine flooring, his architecture lost none of its expressive power and appealed to many who’d found his earlier tough-guy efforts more alienating than audacious. But he was never to everyone’s taste, including Marxist intellectuals averse to an architecture of pleasure, who saw him as an agent of capitalist corporate branding (evidenced by his late-career association with the luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, patron of his overblown Fondation Louis Vuitton of 2005–2014 in Paris, for which he also designed a limited-edition Louis Vuitton “Twisted Box” handbag that cost €3,000).

The first of my twenty-five articles on Gehry (twice as many as I’ve written about any other living architect, plus three catalog essays and a film) was a critique in Progressive Architecture of his unglamorous yet arresting Mid-Atlantic Toyota Distributors Offices of 1979 near Baltimore. To prepare for that piece, I flew to Los Angeles with my wife, Rosemarie Haag Bletter—then a Columbia art history professor and among the first academics to include Gehry in university courses—to meet with him. He instantly seemed like an old friend, gave us a tour of his funky Venice Beach office, and invited us to visit his own much-talked-about house of 1977–1978 in Santa Monica. In 1975 he had married his perspicacious and protective second wife, the Panamanian-born Berta Aguilera, fourteen years his junior. Soon afterward they bought this little 1920s Dutch Colonial fixer-upper, which he proceeded to renovate in a most unusual way.

Taking his cues from the maverick site-specific sculptor Gordon Matta-Clark—who used a chainsaw to carve abandoned buildings into environmental sculptures of extraordinary power—Gehry as much deconstructed his new home as remodeled it. He fortified parts of the pastel-painted, shingled exterior with corrugated steel, wrapped layers of chain-link fencing over other portions in angular planes not seen since Russian Constructivism, and slammed a tilted cubic skylight, which looked as if it had fallen from outer space, into the kitchen. In the interior he exposed walls down to the wooden studs and treated vestigial white plaster patches as though they were Robert Ryman paintings. Paradoxically, this messy mash-up also exuded a cozy domesticity. In due course it became such a tourist magnet that in 2018 the couple moved to a sprawling house designed by Gehry and their younger son, Sam, on a site overlooking Santa Monica Canyon, where Gehry died on December 5 after a brief respiratory illness at age ninety-six.

So thorough was Gehry’s reorientation of architecture as an art form rather than an adjunct of engineering that it’s hard to recall how…

Read the full article on the Review’s website here.

From the Archives: The Martin Filler Digest

I have visited (and loved) Bilbao and Disney. We even have a Gehry here in Seattle. But I saw my favorite when our daughter went to Bard College and sang in his concert hall there. It’s smaller and more intimate, and just perfect. Good article, by the way!