Lately there’s been a spate of novels written by young women that have aremarkably similar plot. I’ve been calling them the “hit me” books. Let’s be less incendiary: let’s call them the “remaster novels.”

They go like this. A woman in her twenties drifts into a relationship with an older man. She lives with roommates, by necessity. She works an entry-level job involving the food or culture industry, but she has artistic aspirations. She is Marxist-ish: she notices class, complains of capitalism, spouts bits of theory. She is queer-ish: she has fantasized about and/or slept with and/or dated women. The older man is generally wealthy, high-powered, charismatic, attractive, good in bed, and—somewhat anachronistically—always white. This is the master.

They fall into an uneasy romance. The master begins in effect to sponsor the young woman, financially or professionally. It seems like he’s still taken—an ex or a wife lurks in the background—and this makes him emotionally unavailable. His distance wounds, but there’s no threat of harmful physical violence in the relationship. The gender imbalance remains, however, intensified by other structural inequities. The novels ensure that he remains more powerful than her by making her weaker on the putative census form: she’s poor/disabled/queer/nonwhite/an alcoholic/mentally unwell/a combination thereof. This familiar script—master and maiden—is established and anxiously examined for its bad politics.

Then it gets flipped. First, the idea of hurting the young woman in bed will come up, sometimes at her explicit request: “hit me.” If the man obliges: presto, mutually pleasurable BDSM. If he doesn’t: drama. Either way, much soul-searching for the young woman: When you say “hit me,” are you doing sexism? Or is sexism doing you? The master’s power is then reduced somehow. He’s humbled. He stumbles. He falls—in love. Now he’s weak, for her. The master is remastered. The lovers are made equal. They both choose to submit, she to dominance, he to romance. A happy ending awaits. And, to crown it all, the young woman will make a work of art, often one that depicts this very relationship as the crucible through which she has achieved her own self-mastery.

There are variations, of course. In Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends (2017), which appears to be the origin of this trend, the master refuses the woman’s invitation to hit her; their post-breakup reunion seems like it may be absorbed into an open marriage. In Miranda Popkey’s Topics of Conversation (2020), we hear stories about different women’s will-she-won’t-she relationships to submission through a central protagonist, who strays outside her “nice” marriage to find a master to knock her around; she becomes a single mother. In Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times (2020), the hitting is deep-throating, the tone is charmingly satirical, the woman is living in Hong Kong, and to our great relief she ditches the dull master for a lovely Singaporean woman.

In Raven Leilani’s Luster (2020), the woman’s final artwork depicts not the master but his wife, with whom the black narrator has a tangled relationship, knotted tighter by the presence of the couple’s adopted black daughter. In Megan Nolan’s Acts of Desperation (2021), the master, well-off but penny-pinching, fails to hit the woman in the ways she wishes; he eventually rapes her when he learns that she’s been cheating on him.

Imogen Crimp’s rather solemn A Very Nice Girl (2022) makes the master a banker and the woman an opera singer, a set-up that occasions cash transfers and meditations on the body as instrument. In Lillian Fishman’s icily cerebral Acts of Service (2022), the heroine’s rape fantasy is fulfilled, but the master mostly hits another woman, the third in their ménage; the novel juxtaposes the two women’s artworks, a literary portrait versus literal paintings of the master. In Alyssa Songsiridej’s lighthearted Little Rabbit (2022), the master is rich because of his ex-wife and is himself an artist—a choreographer; in the end, master and maiden marry both their persons and their art in the form of a collaborative performance.

Sheena Patel’s I’m a Fan (2023), set in the art world, is more about the woman’s obsession with the ex-girlfriend than the master, and the desire to be hurt in bed is denied by her milquetoast boyfriend; it drifts off in a fantasy of getting knocked up to tie the master down. This Happy (2023) by Niamh Campbell is a baroque account of an abject relationship to a sadomasochistic master; the heroine marries another man but leaves him before descending into postpartum mania. She does end up writing the book, though, which we are holding in our wilting hands.

That’s ten novels. (At least.) Ten! What is going on here?

One theory is that these works are part of a recent boom in women’s fiction. According to NPR:

Once upon a time, women authored less than 10 percent of the new books published in the US each year. They now publish more than 50 percent of them. Not only that, the average female author sells more books than the average male author.

It’s hard to say whether this statistical fact reflects a real change, given that the CEOs of the Big Five publishing houses are all still men and most readers have been women for quite some time. But to take another index of literary success, the 2023 Granta Best Novelists list of twenty writers features just four men. Compare this to its first year, 1983, when it featured just six women, and it does seem, as Will Lloyd says, only slightly begrudgingly, in his article “The Decline of the Literary Bloke,” as though “literary fiction written by men is increasingly irrelevant to the culture at large.”

The culture at large tilts womanward of late. “This book. This book. I read it in one day. I hear I’m not alone,” the actress Sarah Jessica Parker wrote on Instagram of Conversations with Friends, which was sold after a seven-way auction and went on to be a best seller. Another, more cynical theory for the emergence of this new crop is that this particular novel’s breakout success led publishers to hunt for “the next Sally Rooney,” and a flurry of eager imitators followed. (Four of the ten writers I’ve named are Irish; two have been anointed “the next Sally Rooney” in print.) The blurbs on these women’s novels are often penned by or refer to one another, such as this comparison-cluster for Crimp’s A Very Nice Girl: “Absorbing and gripping.... Like Raven Leilani’s Luster, Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times, or Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends.” Critical responses that group the novels, including the one you’re reading now, perpetuate the cycle. Run this through the media machine of the like (“if you liked”; “this is like”) and a period style is born.

So far, so familiar. But why “hit me”? Yet another low-hanging theory for this trend is that this is simply what women want now. Every day, I see posts and articles and shows expostulating about the kids these days. They’re saturated with porn. They’re too judgmental. They’re obsessed with their bums. They’re all playing some kind of alphabetical Mad Libs with their gender and sexuality. They’re but a paycheck away from an OnlyFans account. Kink is normal; the real sin is kink-shaming, et cetera.

Do these novels really reflect what it feels like to be a young person in the early decades of the twenty-first century? It certainly looks rough out there. There’s the widespread “heteropessimism,” as Asa Seresin first dubbed it in The New Inquiry; the creeping deflation of Me Too; the threat of financial precarity in a gig economy; the addictive labyrinth of social media, those digital lines on a black mirror. We are choking on all of it—so why not do some choking in bed? Is that the idea? Turn the trauma into pleasure? Maybe this is just the latest-breaking wave of what some have called “fuck-me feminism” or “do-me feminism.”

This assessment feels a bit presentist, though. Pornography, sadomasochism, gender fluidity, fetishism, ass play, breath play, misogyny, bad dates, poverty, dissipation, narcissism, various opiates of various masses? None of it is novel, especially not for the novel. In 1979 the critic Tony Tanner proposed that “the novel, in its origin, might almost be said to be a transgressive mode.” We can easily trace a kinky shadow line through literary history, including such works as Daniel Defoe’s Roxana (1724), the Marquis de Sade’s Justine (1791), Colette’s Chéri (1920), Pauline Réage’s Story of O (1954), Samuel Delany’s Hogg (1969), Marguerite Duras’s The Lover (1984), Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior (1988), and Annie Ernaux’s Simple Passion (1991). But though they poach from it and even allude to it, the recent “remaster novels” are not really joining that smutty countertradition. They’re far tamer—both in their softcore content and, more surprisingly, in their form. They seem totally uninterested in the stylistic playfulness of precursors like Virginia Woolf or Jeanette Winterson or Kathy Acker. No gender-ambiguous narrators or shattered prose or willful plotlessness here.

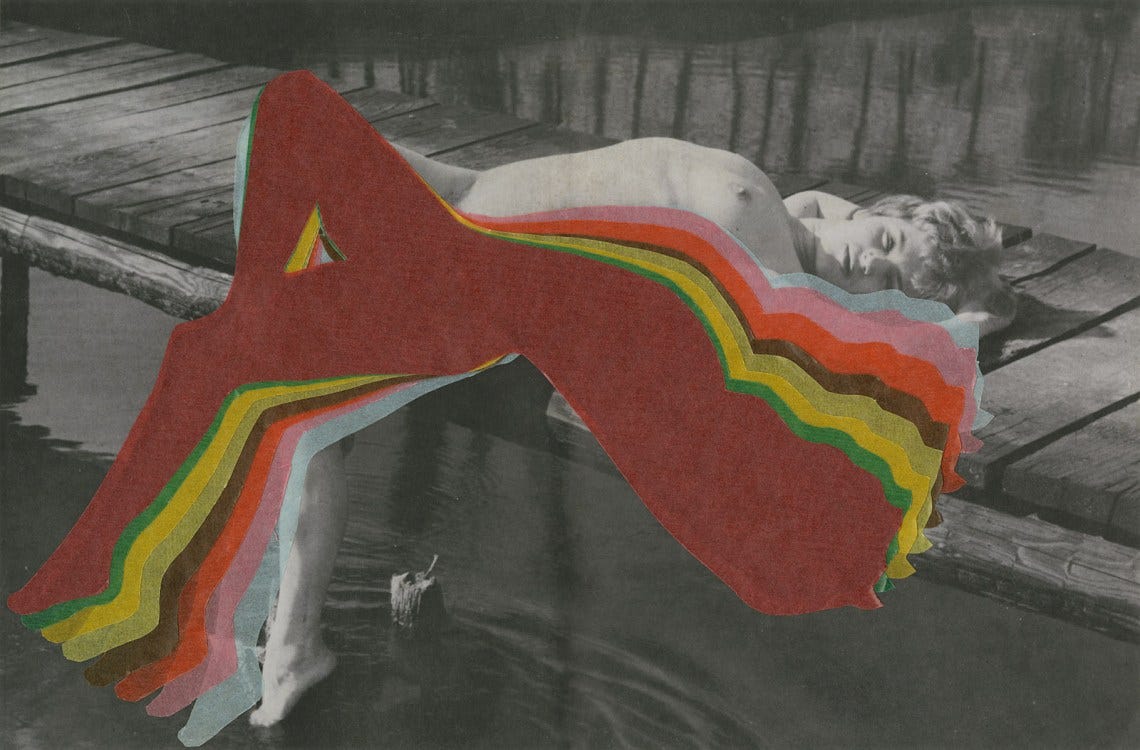

Compare their staidness to two novels published in 2013: Marie Calloway’s what purpose did I serve in your life? and Eimear McBride’s A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing. In both, a young woman seeks out validation and degradation from an older man. Calloway’s narrator wonders if masochistic self-exploitation is third-wave feminism. She describes more than demonstrates her interest in Marxism. She muses self-consciously on the power dynamics of hetero romance: “I’m totally powerless in the face of men.” Yet these novels are far less conventional. Their heroines have sex with many “masters,” in many configurations, which run the gamut from willing to unwilling, for pay and for pleasure. Marriage seems unlikely (McBride’s first “master” is the half-formed girl’s uncle). Calloway features screenshots from real social media posts and pixel-blurred photographs of her nude, BDSM-bruised body. McBride uses a bitty-gritty, flotsam-jetsam prose style. They are both blunt and recursive in a way that feels markedly different from—and more difficult than—the straightforward, televisual style of Rooney & Co.

In the title of her essay in The Drift about this newer batch, Noor Qasim classifies them as “The Millennial Sex Novel,” which seems right. But while the formal features of these novels—transcriptional, self-aware, jaded—do feel millennial, the other authors who regularly wrote about and occasionally relished such dynamics are notably older, and male: Philip Roth, John Updike, Vladimir Nabokov, Henry Miller. And if the New Yorker critic Alexandra Schwartz is right that with Conversations with Friends, Rooney has written a new “novel of adultery,” the classics that she and her peers would seem to be referencing go even farther back: D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1878), Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856).

So if these women are agonistically forging a canon, it’s not a matter of sibling rivalry. They appear to be writing back to “Daddy,” the very same Electra complex they dramatize in their pages. Their aim is to remaster—repeat, remix, take revenge on—that stately master narrative we call The Novel.

Sally Rooney admits to this. …

Read the full article on the Review’s website here.