I’ve always been aware of being an inconsistent personality. Of having a lot of contradictory voices knocking around my head. As a kid, I was ashamed of it. Other people seemed to feel strongly about themselves, to know exactly who they were. I was never like that. I could never shake the suspicion that everything about me was the consequence of a series of improbable accidents—not least of which was the 400 trillion–to-one accident of my birth. As I saw it, even my strongest feelings and convictions might easily be otherwise, had I been the child of the next family down the hall, or the child of another century, another country, another God. My mind wandered.

To give a concrete example: if the Pakistani girl next door happened to be painting mehndi on my hands—she liked to use me for practice—it was the work of a moment to imagine I was her sister. I’d envision living with Asma, and knowing and feeling the things she knew and felt. To tell the truth, I rarely entered a friend’s home without wondering what it might be like to never leave. That is, what it would be like to be Polish or Ghanaian or Irish or Bengali, to be richer or poorer, to say these prayers or hold those politics. I was an equal-opportunity voyeur. I wanted to know what it was like to be everybody. Above all, I wondered what it would be like to believe the sorts of things I didn’t believe. Whenever I spent time with my pious Uncle Ricky, and the moment came for everyone around the table to bow their heads, close their eyes, and thank God for a plate of escovitch fish, I could all too easily convince myself that I, too, was a witness of Jehovah. I’d see myself leaving the island, arriving in freezing England, shivering and gripping my own mother’s hand, who was—in this peculiar fictional version—now my older sister.

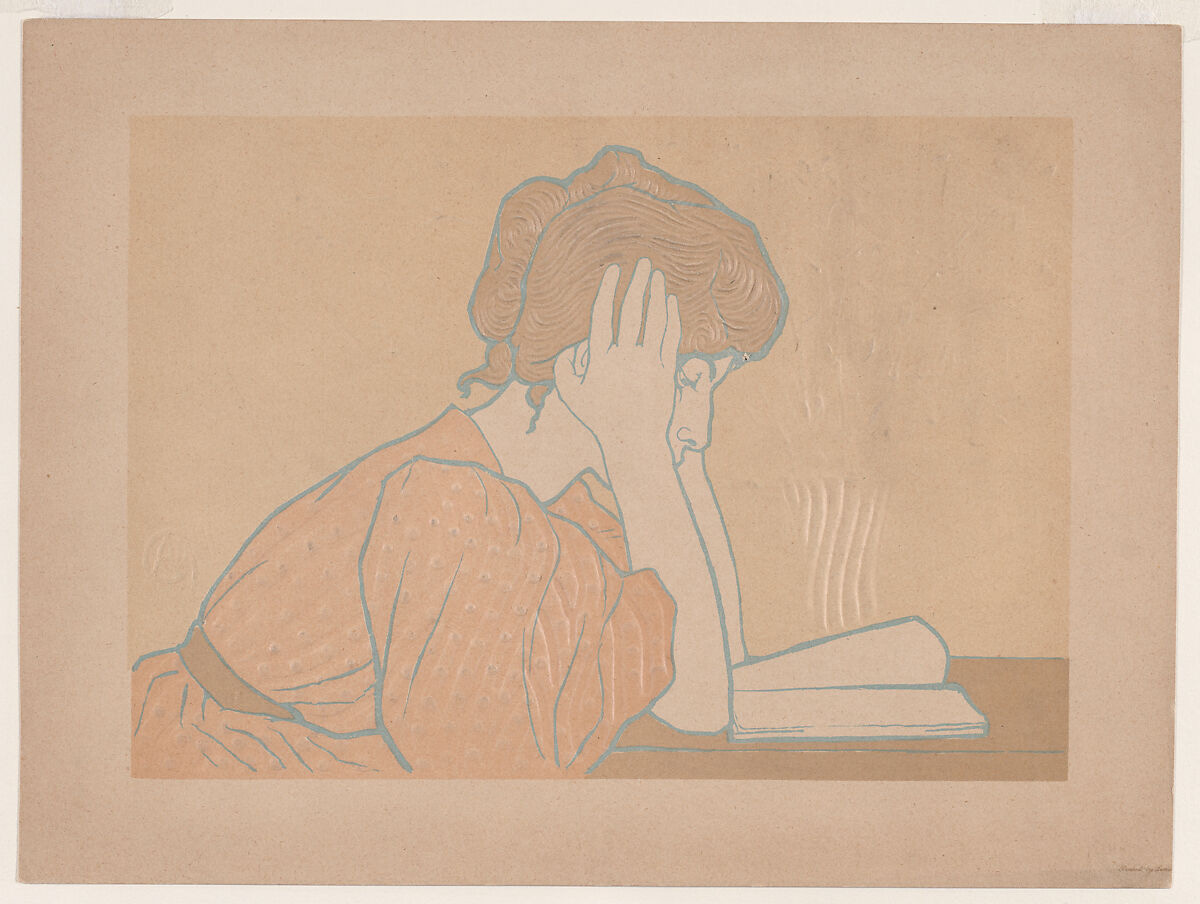

I don’t claim I imagined any of this correctly—only compulsively. And what I did in life, I did with books. I lived in them and felt them live in me. I felt I was Jane Eyre and Celie and Mr. Biswas and David Copperfield. Our autobiographical coordinates rarely matched. I’d never had a friend die of consumption or been raped by my father or lived in Trinidad or the Deep South or the nineteenth century. But I’d been sad and lost, sometimes desperate, often confused. It was on the basis of such flimsy emotional clues that I found myself feeling with these imaginary strangers: feeling with them, for them, alongside them and through them, extrapolating from my own emotions, which, though strikingly minor when compared to the high dramas of fiction, still bore some relation to them, as all human feelings do. The voices of characters joined the ranks of all the other voices inside me, serving to make the idea of my “own voice” indistinct. Or maybe it’s better to say: I’ve never believed myself to have a voice entirely separate from the many voices I hear, read, and internalize every day.

At some point during this inconsistent childhood, I was struck by an old cartoon I came across somewhere. It depicted Charles Dickens, the image of contentment, surrounded by all his characters come to life. I found that image comforting. Dickens didn’t look worried or ashamed. Didn’t appear to suspect he might be schizophrenic or in some other way pathological. He had a name for his condition: novelist. Early in my life, this became my cover story, too. And for years now, in the pages of novels, “I” have been both adult and child, male and female, black, brown, and white, gay and straight, funny and tragic, liberal and conservative, religious and godless, not to mention alive and dead. All the voices within me have had an airing, and though I never achieved the sense of contentment I saw in that cartoon—itself perhaps a fiction—over time I have striven to feel less shame about my compulsive interest in the lives of others and the multiple voices in my head. Still, whenever I am struck by the old self-loathing, I try to bring to mind that cartoon, alongside some well-worn lines of Walt Whitman’s:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

I’m sure I’m not the first novelist to dig up that old Whitman chestnut in defense of our indefensible art. And it would be easy enough at this point to march onward and write a triumphalist defense of fiction, ridiculing those who hold the very practice in suspicion—the type of reader who wonders how a man wrote Anna Karenina, or why Zora Neale Hurston once wrote a book with no black people in it, or why a gay woman like Patricia Highsmith spent so much time imagining herself into the life of an (ostensibly) straight white man called Ripley. But I don’t write fiction in a triumphalist spirit and I can’t defend it in that way either. Besides which, a counter-voice in my head detects, in Whitman’s lines, not a little entitlement. Containing multitudes sounds, just now, like an act of colonization. Who is this Whitman, and who does he think he is, containing anyone? Let Whitman speak for Whitman—I’ll speak for myself, thank you very much. How can Whitman—white, gay, American—possibly contain, say, a black polysexual British girl or a nonbinary Palestinian or a Republican Baptist from Atlanta? How can Whitman, dead in 1892, contain, or even know anything at all of the particularities of any of us, alive as we are, in this tumultuous year, 2019?

This inner voice suspects the problem starts in that word, contain, which would appear to share some lexical territory with other troubling discourses. The language of land rights. The language of prison ideology. The language of immigration policy. Even the language of military strategy. Nor does it seem at all surprising to me that we should, in 2019, have this hypersensitivity to language, given that it is something we carry about our person, in our mouths and our minds. It’s right there, within our grasp, and we can effect change upon it, sometimes radical change. Whereas many more material issues—precisely economic inequality, criminal justice reform, immigration policy, and war—prove frighteningly intractable. Language becomes the convenient battlefield. And language is also, literally, the “containment.” The terms we choose—or the terms we are offered—behave as containers for our ideas, necessarily shaping and determining the form of what it is we think, or think we think. Our arguments about “cultural appropriation,” for example, cannot help but be heavily influenced by the term itself. Yet we treat those two carefully chosen words as if they were elemental, neutral in themselves, handed down from the heavens. When of course they are only, like all language, a verbal container, which, like all such containers, allows the emergence of certain ideas while limiting the possibilities of others.

What would our debates about fiction look like, I sometimes wonder, if our preferred verbal container for the phenomenon of writing about others was not “cultural appropriation” but rather “interpersonal voyeurism” or “profound-other-fascination” or even “cross-epidermal reanimation”? Our discussions would still be vibrant, perhaps even still furious—but I’m certain they would not be the same. Aren’t we a little too passive in the face of inherited concepts? We allow them to think for us, and to stand as place markers when we can’t be bothered to think. What she said. But surely the task of a writer is to think for herself! And immediately, within that bumptious exclamation mark, an internal voice notes the telltale whiff of baby boomer triumphalism, of Generation X moral irresponsibility.... I do believe a writer’s task is to think for herself, although this task, to me, signifies not a fixed state but a continual process: thinking things afresh, each time, in each new situation. This requires not a little mental flexibility. No piety of the culture—whether it be I think therefore I am, To be or not to be, You do you, or I contain multitudes—should or ever can be entirely fixed in place or protected from the currents of history. There is always the potential for radical change.

“Re-examine all you have been told,” Whitman tells us, “and dismiss whatever insults your own soul.” Full disclosure: what insults my soul is the idea—popular in the culture just now, and presented in widely variant degrees of complexity—that we can and should write only about people who are fundamentally “like” us: racially, sexually, genetically, nationally, politically, personally. That only an intimate authorial autobiographical connection with a character can be the rightful basis of a fiction. I do not believe that. I could not have written a single one of my books if I did. But I feel no sense of triumph in my apostasy. It might well be that we simply don’t want or need novels like mine anymore, or any of the kinds of fictions that, in order to exist, must fundamentally disagree with the new theory of “likeness.” It may be that the whole category of what we used to call fiction is becoming lost to us. And if enough people turn from the concept of fiction as it was once understood, then fighting this transformation will be like going to war against the neologism “impactful” or mourning the loss of the modal verb “shall.” As it is with language, so it goes with culture: what is not used or wanted dies. What is needed blooms and spreads.

Consequently, my interest here is not so much prescriptive as descriptive. For me the question is not: Should we abandon fiction? (Readers will decide that—are in the process of already deciding. Many decided some time ago.) The question is: Do we know what fiction was? We think we know. In the process of turning from it, we’ve accused it of appropriation, colonization, delusion, vanity, naiveté, political and moral irresponsibility. We have found fiction wanting in myriad ways but rarely paused to wonder, or recall, what we once wanted from it—what theories of self-and-other it offered us, or why, for so long, those theories felt meaningful to so many. Embarrassed by the novel—and its mortifying habit of putting words into the mouths of others—many have moved swiftly on to what they perceive to be safer ground, namely, the supposedly unquestionable authenticity of personal experience.

The old—and never especially helpful—adage write what you know has morphed into something more like a threat: Stay in your lane. This principle permits the category of fiction, but really only to the extent that we acknowledge and confess that personal experience is inviolate and nontransferable. It concedes that personal experience may be displayed, very carefully, to the unlike-us, to the stranger, even to the enemy—but insists it can never truly be shared by them. This rule also pertains in the opposite direction: the experience of the unlike-us can never be co-opted, ventriloquized, or otherwise “stolen” by us. (As the philosopher Anthony Appiah has noted, these ideas of cultural ownership share some DNA with the late-capitalist concept of brand integrity.) Only those who are like us are like us. Only those who are like us can understand us—or should even try. Which entire philosophical edifice depends on visibility and legibility, that is, on the sense that we can be certain of who is and isn’t “like us” simply by looking at them and/or listening to what they have to say.

Fiction didn’t believe any of that. Fiction suspected that there is far more to people than what they choose to make manifest. Fiction wondered what likeness between selves might even mean, given the profound mystery of consciousness itself, which so many other disciplines—most notably philosophy—have probed for millennia without reaching any definitive conclusions. Fiction was suspicious of any theory of the self that appeared to be largely founded on what can be seen with the human eye, that is, those parts of our selves that are material, manifest, and clearly visible in a crowd. Fiction—at least the kind that was any good—was full of doubt, self-doubt above all. It had grave doubts about the nature of the self.

Read the full article for free on the Review’s website here.

Zadie Smith, from her essay in the NYRB restacked above—-”what insults my soul is the idea—popular in the culture just now, and presented in widely variant degrees of complexity—that we can and should write only about people who are fundamentally “like” us: racially, sexually, genetically, nationally, politically, personally. That only an intimate authorial autobiographical connection with a character can be the rightful basis of a fiction. I do not believe that.”