Since they replaced the diseased portion of my aorta with a knitted Dacron polyester graft, I hear my heartbeat if I turn my head; I feel a pounding in my chest whenever I inhale deeply; I feel new pulses in new locations with new intensity. (The Dacron graft is less dampening than your aortic tissue: natural aortic walls absorb and cushion some of the pulsatile force; Dacron reflects it. This makes the pulse pressure wave travel differently and can amplify heart sounds, such as valve closures.)

Familiar metaphors become literal: when, in the process of repairing an aneurysm at your aortic root, a surgeon touches your heart, you are at risk of developing postcardiac depression, also known as the “cardiac blues.” They don’t know why this is, but it’s in the literature.

I entered the literature when they touched my heart and changed the prosody of my body, and now I must await postoperative heartbreak. Because of the dark and the drugs, I couldn’t, at first, tell the nurses apart, so they became one nurse with changeable tattoos on her muscular arms: octopus, pagoda, fern. The forms flickered and morphed as I watched; the tattoos were trying to tell me a story—like in that animated musical, where the inked figures act out scenes on the broad chest of the demigod. What was it called? Perioperative memory loss.

You’d placed my phone on one of those plate chargers near the window so I could talk to it. I’d forgotten that our daughter, before the surgery, had set the AI voice to Santa Claus. So: “Ho, ho, ho, you’re thinking of Moana.” And when I asked it about the altered acoustics of my body, Santa got very quiet, a kind of “’Twas the night before Christmas” whisper: “My friend, the Dacron graft is less dampening than your aortic tissue...”

This is a test of how changes in my pulse pressure waves have altered my sentence rhythms. If I can bring those new rhythms into right relation with the experience I’m trying to describe—if I can make what I think of as my Dacron sentences capture something of those hospital nights—then maybe I’ll have made progress toward integrating the experience, toward making it shareable, and maybe this will rob it of some of its traumatic force, and help me prevent, or at least work through, the cardiac blues, which I feel coming, which I hear approaching at the time of writing on the hooves of my new heartbeats. I am late in week two of recovery.

I’m surprised to find that, despite my vanguard pieties, I do think of writing as therapy. I think of it as cardiac rehab.

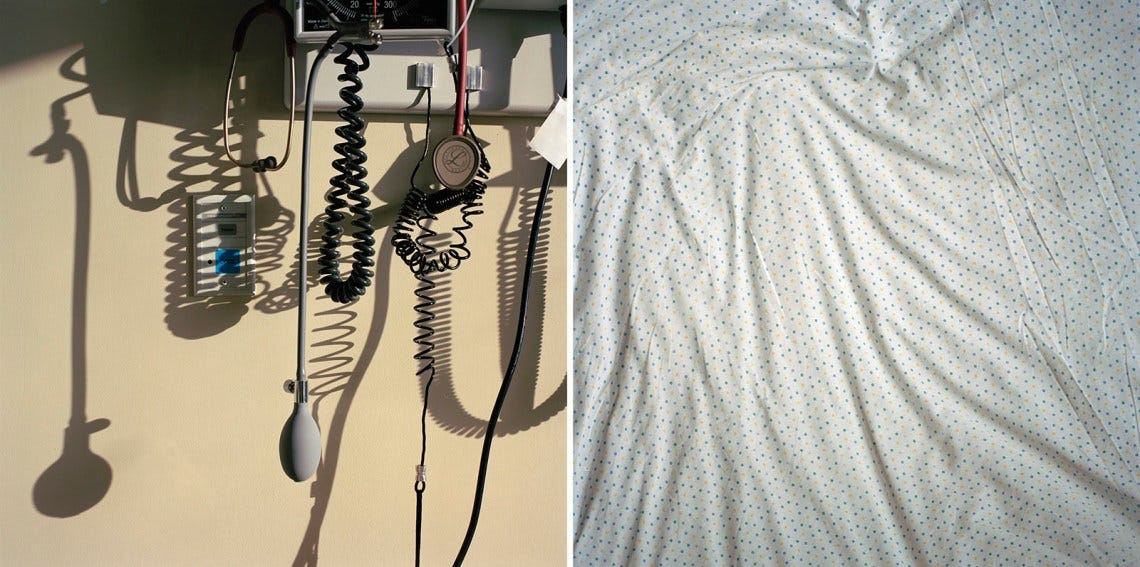

There is a central venous catheter in my neck. Two larger chest tubes protrude from below my sternum, draining air, blood, but also a straw-colored liquid from the spaces between my lungs. It drains into a clear plastic box on the floor. There are fine stainless steel pacer wires that rest on the surface of my heart and exit my body somewhere beneath the sternotomy incision. I can’t see these; I think they’re taped to my skin; I think they pick up, in addition to cosmic background radiation, small waves in the ether formed by the heart sounds of fellow patients in nearby rooms. (All the rooms in the cardiac unit, which is on the fourteenth floor, are private.) There is an arterial line in my wrist, various peripheral IV lines in my hands. I am being given vasopressors for low blood pressure and insulin for high blood sugar and who knows what other liquids for what other purposes. I am probably receiving “blood products,” a phrase impossible to unhear. A Foley catheter draws my urine into another clear box on the floor.

Despite the neck tube, I can turn my head to the left. But when I turn it, when my cheek comes to rest on the pillow, my consciousness remains where it was. My grammar can’t hold it, how I’m still staring at the ceiling while my face is turned toward the window, toward the cot on which you sleep outside the literature.

You slept surprisingly well beside the window, despite all the beeping, the coming and going. A deep and necessary and protective sleep because of all the terror you’d been carrying, all the work you’d been doing to support us. You know what happened during the days but I’m working through a long postsurgical night. You know who you are but at the same time I want you, the you, to expand: I want the pronoun to have a relaxation phase (diastole), where anyone can be on the cot, look out the window that opens onto the East River. The continuous cycle of pronominal expansion and contraction is the heart of writing for me, it is the time of writing, the filling and emptying of the chambers of the art. As are its arrhythmias.

I feel permitted to use these metaphors and say these unoriginal things anew because they sawed open my chest and stopped my heart and changed the prosody of my body. And I’m hardly alone; I have joined a community: each year they do this—at least the sawing and the stopping part—to more than two million people, which is about the population of the heart of Paris. I picture a Paris where everyone within the city limits has had open-heart surgery, an open city. I am in the hospital bed facing left but staring at the ceiling hitting the little button that gives me narcotics and imagining that even the Parisian birds and mice and squirrels have had their hearts stopped with a cold potassium solution so that surgeons, who have themselves only recently had their ribs pried apart, can do their delicate work in a still and bloodless field.

The intense emotional lability that immediately follows the procedure is not to be confused with the cardiac blues, which are a duller, deeper, postpartum-like despair. That first night, while (the) you slept, the composite nurse helped feed me ice chips and Jell-O with a plastic spoon. I wept and wept and laughed at my weeping, which caused excruciating pain—try not to cough, laugh, or sneeze in the first days following your sternotomy. I cannot tell you how delicious it was—orange Jell-O, ice pellets, tear salt, the height of Parisian cuisine; I cannot tell you how I loved the nurse who spoon-fed me so gently in the dark.

But then she vanished; I heard running in the hall, where a blue light was flashing. Code blue, cacophony, but also muffled somehow—hushed voices, soft thud of sneakers, rustling of scrubs, the squeak of a crash cart—as if the rapid emergency response already contained an element of mourning. I managed to reach the Styrofoam cup and drink a little of the ice melt on my own, just a little, as I’d gained twelve pounds from fluid already and couldn’t recognize my hands for the edema. I imagined a blue arc extending from my pacer wires to those of the person whose heart had stopped.

Unconscious during the insertion of the major tubes and wires, I was awake for their removal. (Actually, I wasn’t awake for the removal of the endotracheal tube, which happened when I was still in the operating room, and I have only a fading dreamlike recollection of their pulling out the nasogastric tube, as I’d barely begun to surface from the anesthesia; my eyes were closed. But still I recall something akin to that trick where clowns or magicians produce endless silk scarves from a pocket or sleeve; the NG tube is four feet long.) I remember the other removals as happening while you slept, although that’s wrong—only the tube in my jugular came out in the literal dark. I probably remember it that way because you weren’t there; I insisted you leave the room; I didn’t want you to witness my decannulations; I’ll write it all down for you later, I promised in my head. My only defense against reality: to transform it into literature.

Each removal constituted progress, a step down in the intensity of care, a step toward the restoration of the human, but I was terrified of the extractions, having read a hundred posts on Reddit claiming that the removal of the tubes was the most traumatic part of the entire “controlled trauma” of valve-sparing aortic root replacement.

Bless the nurse (by this point the nurses began to individuate) who removed the line from my neck—bless her for the clarity of her speech and the decisiveness of her movements. I recall her voice and touch vividly, though I never really saw her face. She adjusted my mechanical bed so that I was in a mild version of what is called the Trendelenburg position, meaning my head was slightly lower than my chest. She established a sterile field around the line and deftly removed the tape and cut the little stitches that held the device in place. And then she told me that I could either take a deep breath and hold it or begin to hum.

Hum? Yes, she said, hum. It hurt to breathe deeply, to hold my breath, but the idea of humming embarrassed me, as if she’d suggested I might sing. Would you like me to hum with you? she asked. Why don’t we hum together, she said. (Bless all medical practitioners who close, however briefly, the divide between the healthy and the sick, subject and object, who don’t look down at your broken body in the Trendelenburg position but instead draw alongside you in your suffering.) Yes, please, I said. And she began humming and I joined her in this proto-speech, this proto-song, and this increased my venous pressure and closed my vocal cords so as to prevent an air embolism as she pulled in one perfectly smooth gesture seven inches of tubing from my jugular. Then she held gauze over the exit site for several minutes. (I was on blood thinners.) You have been a great comfort to me, I kept repeating.

I think many hours must have passed, maybe a day or more had passed, before a young resident arrived, along with a supervising fellow, to remove my chest tubes, but I remember all the extractions as taking place one after the other. I recall that the supervising fellow told me that I might want to dispense some narcotics with my little clicker before “the big event.” I don’t remember their faces; I remember almost none of my caretakers’ faces, not only because of shock and drugs, but also because my vision was disturbed by migraine-like distortions during the entire hospitalization—scotomata and scintillating floating jagged forms (the latter even when my eyes were closed). They said this could be attributed to any number of factors: inflammation, medication, cardiopulmonary dynamics, intracranial pressure shifts, etc. These symptoms didn’t particularly interest them; they considered them irrelevant from a cardiac perspective, since they decided I probably wasn’t having strokes. Also, I wasn’t wearing my glasses.

The young resident seemed competent to me, steady-handed as she removed the dressing and cut the stay sutures around the tubes, but she was learning, I was being learned upon, spoken about instead of to, all of her speech was addressed to her supervisor, and as a result I felt thingly under her touch, reduced to my material. I tried not to think of the anatomy lessons of Rembrandt and Eakins, all those students grouped around a livid corpse. (My visual memory—usually poor—was eidetic in the hospital.) The only thing she said to me directly was: OK, on the count of three, hold your breath or hum. I held my breath. …

Read the full article for free on the Review’s website here.